As we fling ourselves into this stage of exploration, a stage of self-guided archival immersion punctuated by workshops and meetings, I have grown to embrace the nebulousness inherent in any research process, not least for a digital humanities project. In fact, the conversations that we have had this past week reinforce the idea that each research project, either traditional or digital, is a unique undertaking. Unlike the neat charts delineating “the components” of the research process and pointing out a progression with helpful arrows, the reality of research design is a much more complex mingling of “things.” Such things typically include research questions, goals, methods, conceptual framework, and validity (see Trevor Owens’ blogpost here), which constantly interact with each other. On second thoughts, “interact” is rather vague and sterile, isn’t it? As I’m sure we will discover in the next few weeks, they will illuminate each other, be in tension with each other, guide each other, interrogate each other; they will open some doors, shut several, keep a few ajar, lock some others, or eliminate the concept of doors entirely…

Well, that escalated quickly.

My keyword from last week, “fluidity,” applies now as much as ever. In fact, as we begin to learn about tools for digital exhibits and mapping, I find that a reasonable answer to my questions last week regarding where is the best place to start (with research questions, digital tools, interesting ideas?) is this: just start. And follow your heart/head. Yes, this is cheesy, but in a research context where time and effort are in great demand, it is important to not just pick a topic that sparks one’s interest, but to also have the courage to let tidbits lead you down a footpath with an indeterminate destination. Who really knows the destination at this point anyways?

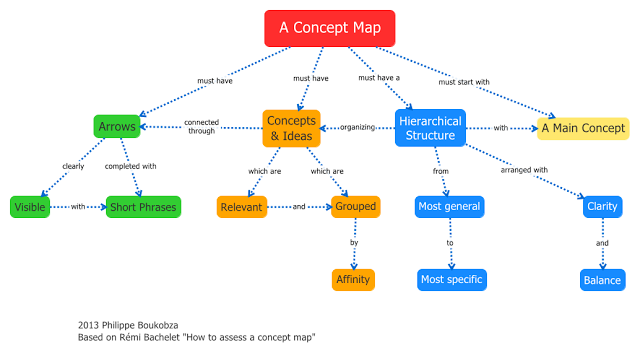

With all this in mind, it is just perfect timing that we made our first concept maps this week. Concept-mapping is an organization tool for brainstorming. A quick Google search yields diagrams of concepts, consisting of boxes and circles connected to each other in a variety of relationships.

For me, who is still a child at heart, concept-mapping is basically making my own spider web. Each string can branch out to another network, connect unlikely objects, or simply hang in space. In a workshop with two Research & Instruction librarians, we learned how to incorporate concept maps into the process of generating research questions. And just like any type of research, the goal of a brainstorming session is to generate without discrimination, which means learning how to eliminate the adjectives such as: is it a trivial question? Too vague? Too vague? Too specific? Too random?

At this stage, asking questions is key. As we start to spend time with tools such as Omeka and TimeMapper, I am less concerned about how to make this a digital humanities project than just thinking about how this project will materialize. I think a Five-College Digital Humanities (DH) post-bac put it best when he told us that digital humanities simply provides a lens with which to approach research. We spend additional time to learn a variety of digital tools, but the essence of the research process remains the same as that of traditional scholarship: immerse oneself in the material, consult ancillary sources, brainstorm questions and ideas while minimizing self-censorship, thinking critically, embracing periods of confusion and self-doubt, figuring out ways to organize information- all with the hope of catching sparks.

I definitely agree about seeing digital humanities as a lens through which to approach research as opposed to seeing it as a completely different form of research altogether. First it does take the pressure off of coming up with something thats drastically different from anything we’ve done before.

Fluidity is a running theme of the internship, and I have a feeling it will still apply almost as strongly at the end of the internship as it currently does now.